(Image by Eric Andresen used under Creative Commons license via)

(Image by Eric Andresen used under Creative Commons license via)

“Emily Sanford speaking, how may I help you?”

“Yeah, hi, I just got put through to you by one of your coworkers, and that guy can barely speak a damn word of German! Why do you hire foreigners? Because they’re so cheap?”

“I’d be happy to help you if you could tell me why you are calling, sir.”

“I need to ask about where to distribute some flyers your company mailed me, but I really want to know first why on earth you hire foreigners? I mean, seriously? Is it to save money?”

I pressed him for the details about the flyers, suppressing the urge to blurt out something in German to the effect of, “I American. I no understanded what you say me in Deutschy language.”

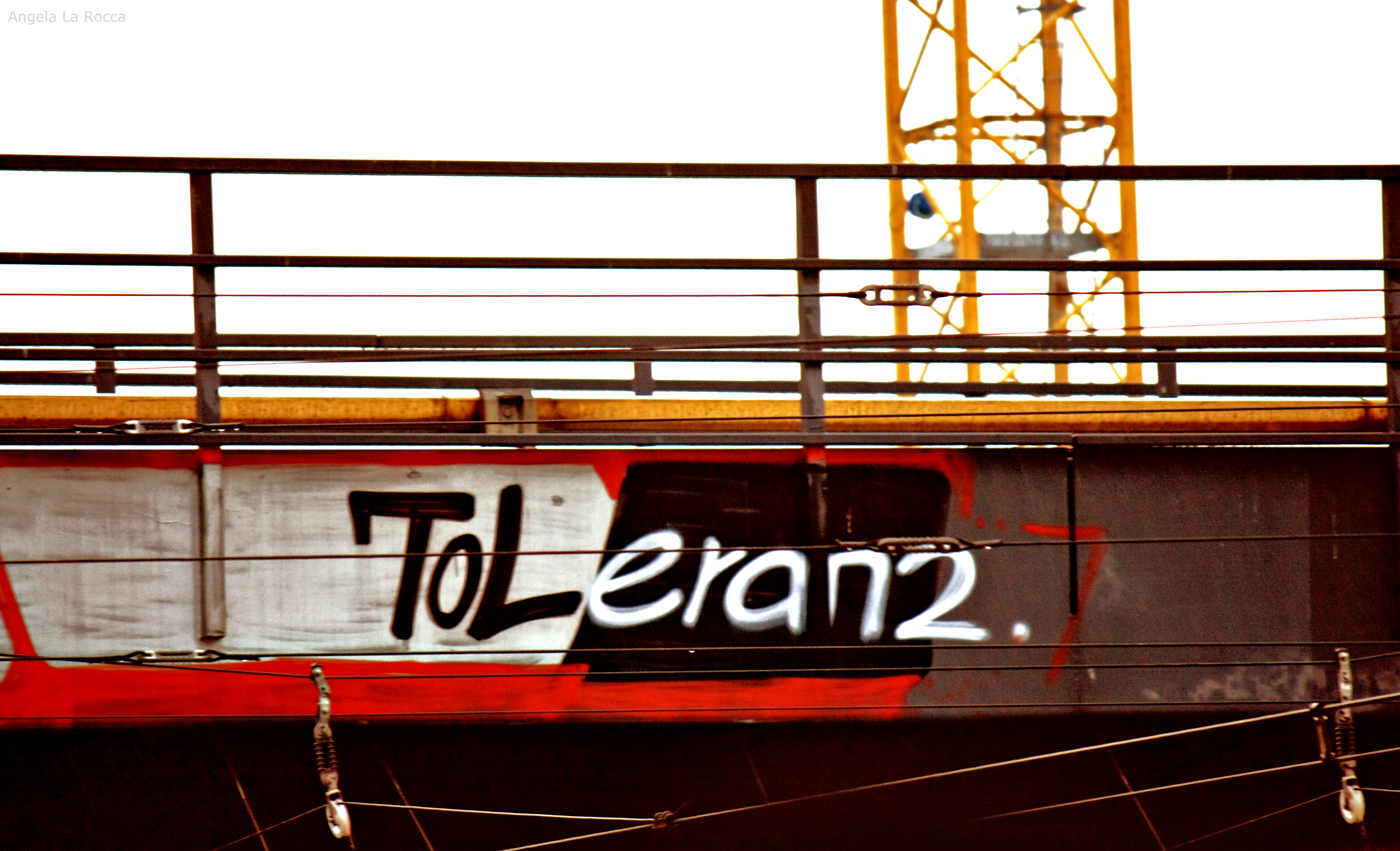

Contempt for immigrants who can’t speak the local language at the C1 Level or higher seems to pervade every country. I’ve witnessed an initiative to make English the official language of my parents’ tiny village in Upstate New York after some white farmers heard two words of Spanish on the street, and I’ve been yelled at here in Germany by surly locals for speaking English in public. These complaints are usually steeped in the explicit or implicit stance that if you can’t speak the language, you shouldn’t be here.

Yet speaking a second language is unlike any other skill. Plenty of fiercely intelligent people are terrible at foreign languages and, unlike being terrible at arithmetic or project management, this weakness will render any of their other talents virtually invisible if the job market does not operate in their mother tongue. Speaking the local language flawlessly and eloquently is the best bet to integration in any society. And if it doesn’t happen to be a language you grew up speaking, it’s a lot of work.

I speak German, French, Russian, Spanish, Swedish, and Dutch, but “speak” is a relative term. I can hold basic conversations in Russian and Spanish, but they’re always peppered with errors. (I’m probably the American equivalent of the intelligible but amusing foreigner who says things like, “I vant you to come sit on de table.”) A few years of self-teaching have led me to understand almost anything written in Dutch, but I can’t understand the nightly news and I can’t say anything not in the present tense. My in-laws in Stockholm sweetly praise whatever I dare to say in their language, but I miss most of the details of whatever they say among themselves. After starting a book called Swedish In Three Months seven years ago, I’m still on chapter four.

I’m fluent in German and French, but “fluent” is too simplistic a word for the complexity of what it denotes. My German feels about as good as my English was back when I was in middle school. That is, I can say almost anything I want to say, but I sound a lot less diplomatic and nuanced than I would like to. I still learn new words every day. (Added to my vocabulary this week were “chisel,” “epic,” and “sexual exploitation.”) Explaining an intricate issue like a budget report to a superior at work can still make me falter. I occasionally hear myself using the wrong gender or preposition, an instant giveaway that I’m foreign. And because double-digit numbers in German are said in reverse order (e.g. “twoandthirty” instead of “thirty-two”), I hate taking down numbers. Always have and always will.

This is why it would be deceptive of me to simply say, “I speak seven languages.” To Brits and Americans, it sounds like bragging, and to Europeans, it sounds suspicious. After all, it’s an unspoken but well-known fact that Brits and Americans who fancy themselves cosmopolitan love to exaggerate whatever knowledge of a foreign language they have, especially when they’re in the company of those who can’t possible test them on it. As British-Canadian satirist Christian Lander writes at Stuff White People Like:

… two years of college Italian does not confer fluency. For the most part, these classes will only teach a white person how to order food in a restaurant, ask for a train schedule, and over pronounce words when they are mixed into English. Amazingly this small amount of proficiency is more than enough to warrant inclusion on a resume under “spoken languages.”

… When you hear a white person say that they speak your native language, you will probably think it’s a good idea to start talking to them in said language. WRONG! Instead you should say something like “you speak (insert language)?” to which they will reply “a little” in your native tongue. If you just leave it here, the white person will feel fantastic for the rest of the day. If you push it any further and speak quickly, the white person will just look at you with a blank stare. Within a minute you will notice that blank stare has shifted from confusion to contempt. You have shamed them and your chance for friendship is ruined forever.

Finally, though they won’t admit it, white people do not believe that learning English is difficult. This is because if it were true, then that would mean that their housekeeper, gardener, mother-in-law … are smarter than them. Needless to say, this realization would destroy their entire universe.

Indeed, my linguistic repertoire doesn’t sound at all impressive to the 216 million people around the world who speak four languages or more. Most of these people live in Africa and, unlike me, their range always encompasses completely unrelated languages like French and Bangangte, or English and Wolof. 45% of my Facebook friends speak two or more languages well enough to say or describe whatever they want to say. For them, and half of the people on earth, speaking more than one language is like knowing how to drive or swim. Sure it requires dedication and practice, but it’s not something you flaunt once you learn how to do it. You just do it.

Conventional wisdom says it’s best to be complimented on your language skills by a native speaker. But if that native speaker is monolingual, they will only notice what you can’t do. It takes a polyglot to appreciate how far along you are because they know just how much work goes into what you’re trying to accomplish. Anyone who’s lived 24 hours a day in another language knows about the headaches, the falling into bed exhausted at 8 pm, the horrors of meeting someone who talks fast.

Tech reviews across the Interwebs have been abuzz this year about a new language program called DuoLingo. The online program claims to be revolutionizing the way Anglophones learn other languages via the addictive nature of video games. That DuoLingo inspires passion and dedication is wonderful, and after checking out the advanced German program, I’m impressed with how authentically modern the dialogue is. (None of that old school drivel still found in too many online programs: “I am charmed to make your acquaintance. Which way to the discotheque?”) But I’m skeptical of the company’s insistence that you can learn a language without ever speaking to people.

Does the game teach you how to develop an intelligible accent? Does it teach you how to dive into a dinner conversation with sentences shooting at you from every direction? And, perhaps most importantly, does the game warn you about the crucial cultural connotations of certain words? To cite just a few examples, in German a “Pamphlet” isn’t just a pamphlet, it’s a manifesto. The word “deportieren” means what it sounds like except it’s only used to describe someone being sent away to a concentration camp. And you will come off as crass if you ever call a German woman “Fräulein.” As with all my knowledge of German slang, I learned these lessons from German people, not dictionaries. Language is culture and there are no cultures without people.

And just like every culture on earth, every language is a moving target. What sounds hip and what sounds sophisticated and what sounds rude and what sounds stuffy differs from generation to generation, from place to place, and from person to person. It’s exhausting, but it’s also pretty cool. In an increasingly homogeneous world, the most resilient differences are linguistic. American tourists are often disappointed to discover that businessmen in London dress more like Bill Gates than Winston Churchill, or that women in Barcelona don’t walk around with roses clenched between their teeth. But no matter the visual monotony, their ears are guaranteed to be confronted with new music.

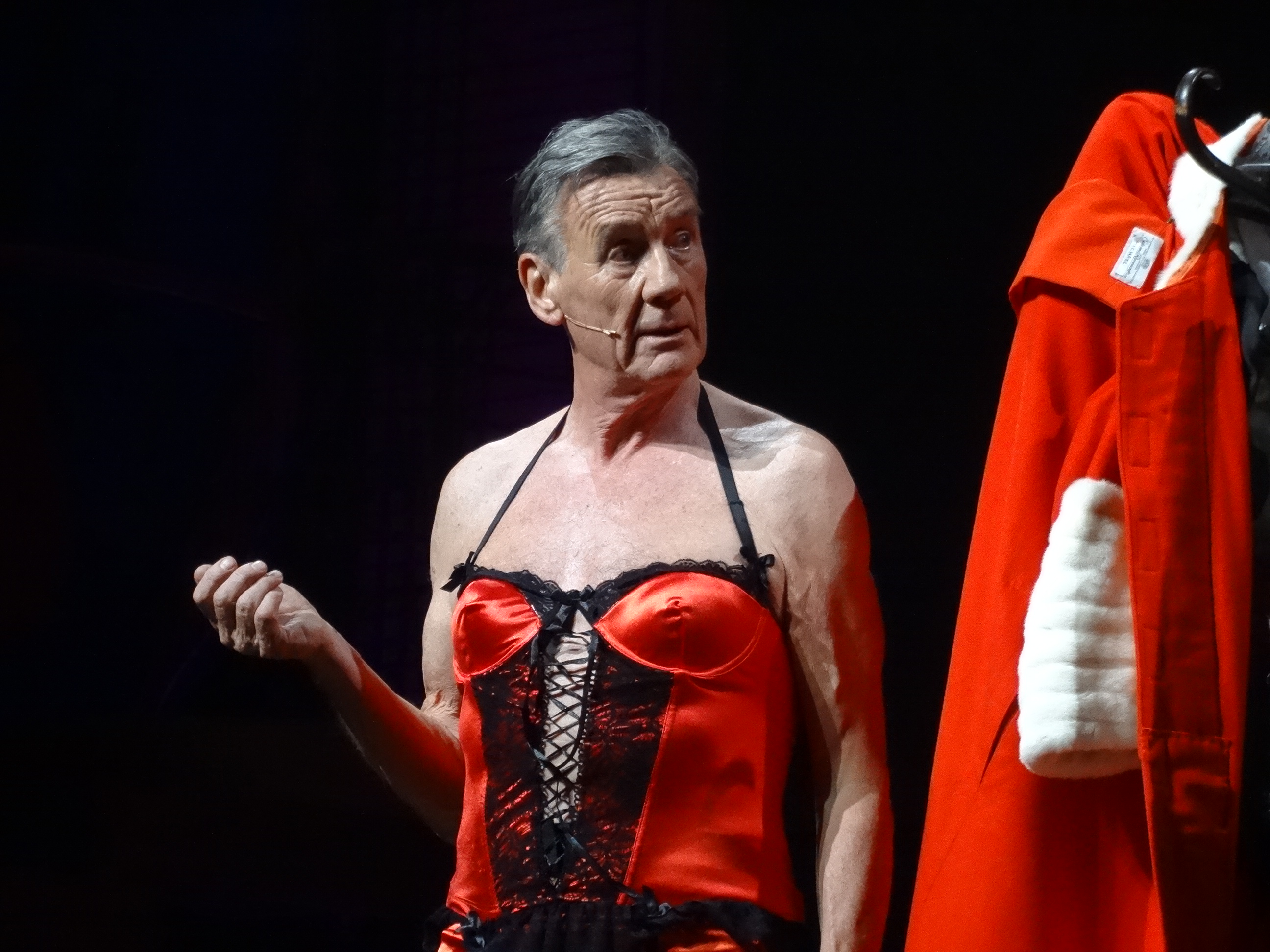

Yet, despite its shortcomings, I suspect that DuoLingo’s personless approach to foreign language learning is exactly what many bilingual wannabes yearn for. In my experience, the number one reason adults will avoid or give up learning a foreign language is not that they dislike grammar or are overwhelmed by accents – it’s that whenever you try to speak a new language, you are bound to be laughed at.

Unlike learning to dance or sew or build a shed, you can only master a language by repeatedly practicing in the company of experts—i.e., native speakers—who are not paid to have the patience of teachers. No matter how good you are, the moment you venture out of the classroom to talk to others, someone will smirk at you and someone will correct you and someone else will get frustrated with how long it takes you to say the simplest thing. Someone is bound to make fun of you. And adults do not like being made fun of.

They don’t like being corrected mid-sentence or being told they sound “cute.” It reminds them of being back in school, and they’ll do anything to avoid it. This is why trying to learn a foreign language from a romantic partner often puts strain on the relationship. Sure it’s fun to proudly whisper “I love you, my sweetness” to your boyfriend in another language. But it’s exasperating to try to discuss a film you just watched together and see a smirk creep across his face as you say, “I think that part not so good, but other part a little, little okay, but it hard understand why the… the… the… what’s the word?”

Adult pride can be so sensitive that there are debates as to whether or not it’s rude to correct a grown person’s linguistic mistakes outside of the classroom. I’m of the camp that insists on gulping down our pride because, as my French hostess told me my third day in Provence, “Do you want to learn French or don’t you?!” Her commitment to this credo was proven when she shouted grammatical corrections to me from another room while I was talking on the phone.

But there are other conflicts where the rules for etiquette are not so clear. My partner and I recently told a Danish-German couple about our latest trip to Stockholm. We had had a few tiffs about my being left out of the Swedish conversations and his relatives being left out of the English conversations.

Our friends nodded knowingly. “The answer to that problem,” the Dane said with a grin, “is that it’s incredibly rude of them to leave you out of a conversation by speaking a language that’s hard for you, and it’s also incredibly rude of you to insist that everyone switch to a language that’s hard for them just for your sake.”

Indeed, being excluded from anything is a nasty feeling and nothing excludes like a foreign language. Then again, once a couple is fluent in more than one common language, the ability to speak in code is a pretty sweet reward. (Ex: “Do you mind if we change the subject, honey? I don’t want to hear him get going on this again… ”)

Many adults insist that they would have become fluent in a foreign language if only their parents had paid for early lessons because kids pick up languages better. There is truth to this argument – children living abroad for a year or more are indeed more likely to become fluent than their parents are, but few understand why. I do not believe the pop science assumption that kids have an easier time learning languages because they are neurologically predisposed. Studies at Cambridge University—and my own experience as an English teacher in Berlin pre-schools—show that kids above the age of three start off a new language with the same bad accent and tendency to make mistakes as adults do. The three advantages children do have over adults are all social.

First of all, while they don’t exactly enjoy being laughed at, kids are far less self-conscious about making mistakes than teenagers and adults are. Secondly, immigrant and expat kids can easily be immersed in the local language simply by being enrolled in school, as opposed to their parents, who must first land a job in the language and therein already demonstrate some proficiency. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, kids have a lot less to learn to achieve fluency in their age group than adults do. A first grader’s mastery of a language involves being able to talk about Disney films and their favorite flavor of ice cream and all that other stuff found at the intermediate level of any language course. Fluency for an adult means being able to engage in debates about the next election or to write business letters or to make witty jokes with a killer punch-line, all skills for which we each need 12 years of schooling just to master in our first language, never mind a second one.

Learning a foreign language takes a lot of patience and a sturdy ego. In return, it endows you with empathy for students of your own language. And with this empathy it is not rude to smile at a non-native speaker’s mistakes or to poke fun at languages and accents. It’s hilarious to hear someone with a thick German accent try to say “weather vane” (usually comes out as “fezzerwane”), and it’s just as hilarious to hear Americans try to say, “Geschlechtergleichberechtigung” (“gender equality”).

When I was staying in Tokyo two years ago, my friend Kazumi would call me to dinner. “Em-i-liiii!”

“Hai!” I’d reply with exorbitant enthusiasm.

This always made her and her fiancé burst into giggles. “So cute how you say, ‘Hai!’ ” she would smile.

“So cute how you say my name,” I’d smile back.

This exchange would not be so innocuous if one of us were portraying the other’s accent as a sign of stupidity, or complacently refusing to ever leave our own linguistic comfort zone.

When Brits complain about the invasion of other languages and dialects, they ignore that millions throughout Asia, Africa, Oceania, the Americas and the Caribbean gave up their first language for the King’s English lest they face punishment. When Americans insist that they shouldn’t have to learn another language because immigrants and foreigners should learn theirs, they ignore that more than three-quarters of us are descended from ancestors who had to learn English as a second language. Many Americans seem to believe they did it so that we wouldn’t have to. But if they want to fully comprehend what exactly their ancestors achieved and what exactly they’re asking of immigrants today, then they will have to try to do it themselves. If I had wanted to be truly fair to my caller so angry about my coworker’s German, I would have switched into my own language and waited to see how well he fared.

Learning a foreign language is not about picking up enough exotic words to be able to show off at dinner parties. It’s about understanding why foreigners make mistakes in our language by exposing ourselves to the mistakes we are bound to make in theirs. It’s about both the guest and the host, the tourist and the immigrant, not giving anyone attitude for failing to speak flawlessly to them in their own language. It’s about forging a path to greater empathy, until it expands into your own backyard and all around the world.

Tags: Culture, Ethnicity, foreign language, Immigration, Language, Minorities, Nationality, Second Language, travel

(Image by Angela Schlafmütze used under CC 2.0 via)

(Image by Angela Schlafmütze used under CC 2.0 via)

(

(