Here’s a shocker: North Americans don’t like activists, especially feminists and environmentalists. Results from a study featured in The Pacific Standard show that these groups are associated with an abrasive, in-your-face approach to politics, and this repels more people than it attracts. Reporter Tom Jacobs urges these groups to change their tactics if they want to get anything done, while Alexandra Brodsky at Feministing has taken umbrage at any call for women to “hush up.” Jacobs has my attention. As someone who’s constantly clogging her Facebook friends’ Newsfeeds with social justice editorials, I’m happy to hear from anyone who can tell me how to entice more people to join the discussion.

Here’s a shocker: North Americans don’t like activists, especially feminists and environmentalists. Results from a study featured in The Pacific Standard show that these groups are associated with an abrasive, in-your-face approach to politics, and this repels more people than it attracts. Reporter Tom Jacobs urges these groups to change their tactics if they want to get anything done, while Alexandra Brodsky at Feministing has taken umbrage at any call for women to “hush up.” Jacobs has my attention. As someone who’s constantly clogging her Facebook friends’ Newsfeeds with social justice editorials, I’m happy to hear from anyone who can tell me how to entice more people to join the discussion.

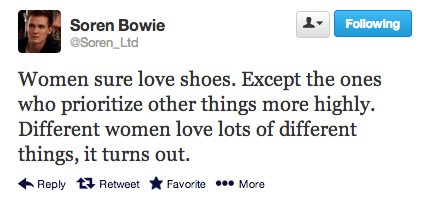

Activism is recognizing injustice and inequality when you see it, and taking the time to ask, “Why?” It doesn’t have to be angry. But several of my friends echo the results of the study, saying they’re turned off by the way so many activists—feminists in particular—walk around like ticking time bombs, ready to explode at anyone who dares disagree with a woman ever. One of these friends cited a feminist who once told her, “The problem is people don’t like my writing because I’m just too controversial for them.”

I can see how that kind of self-righteousness would fail to impress, and I can also see where it comes from. Emotions run high whenever we try to talk about injustice and inequality because these are issues that threaten personal safety and pride. Debaters on both ends of the political spectrum all too often tend toward the obstreperous, topping off their arguments with the age-old threat: “You don’t want to make me angry.”

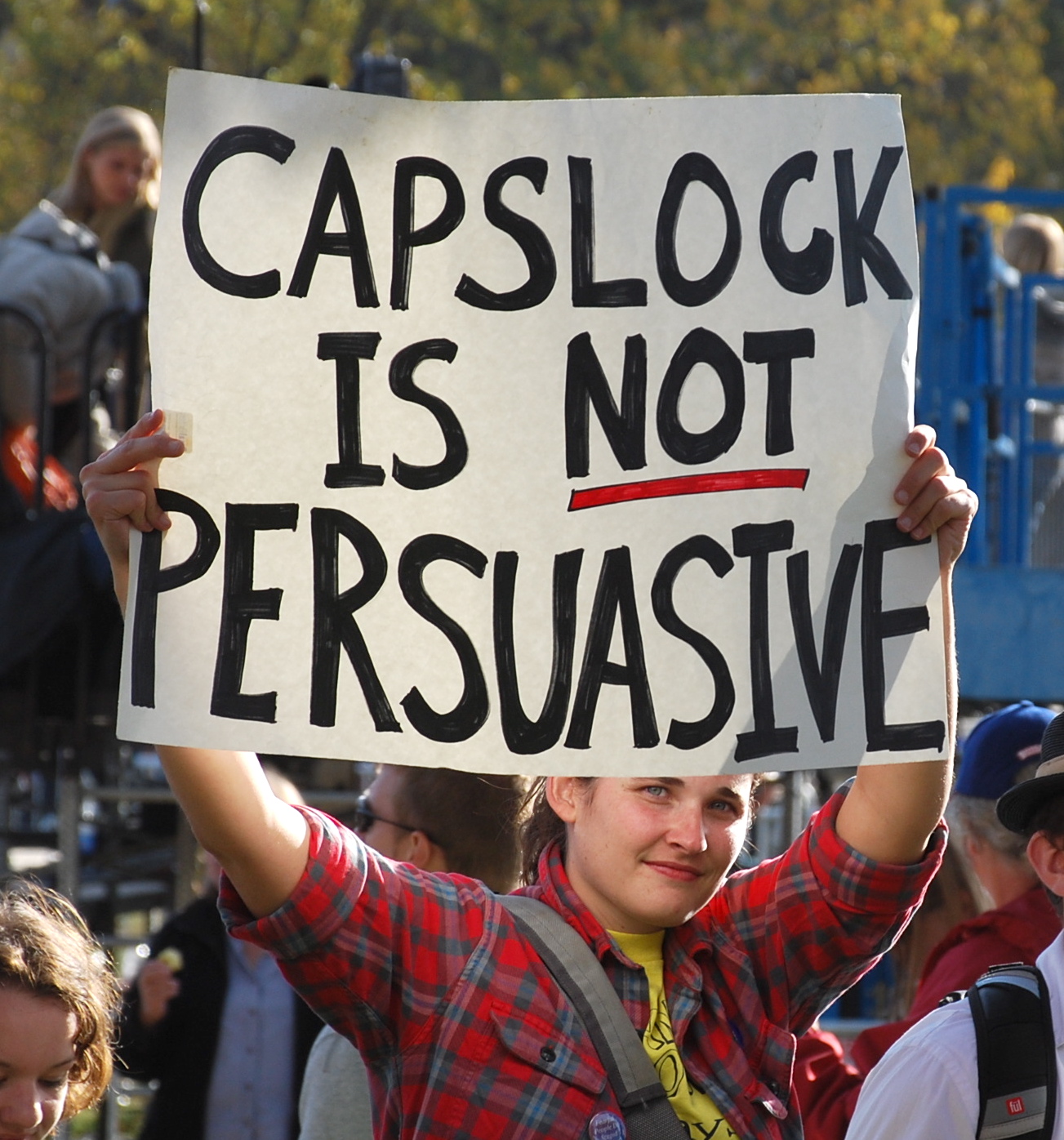

To which I must say, You’re right. I don’t. Because you can be rather boring when you’re angry. Speaking up requires some degree of bravery, but simply getting angry requires no talent whatsoever. A toddler can get angry. (Calling someone a Nazi requires even less skill.) Hollering until your opponent cowers may feel like you won the debate, but it usually means you’ve humiliated them, which will cause them and their supporters to hate you and your beliefs more than they did prior to the encounter. If you’re concerned with no one’s opinion but your own, then your activism isn’t about seeking justice. It’s about seeking attention. And anyone can play that game.

That said, it is unfair of anti-feminists to use a few belligerent narcissists as an excuse for dismissing an entire movement, for denying inequality and injustice exist, for refusing to listen to anyone who speaks up about it. In reaction to this year’s spate of female celebrities claiming “I’m not a feminist, but—”, the great Mary Elizabeth Williams wrote:

Ladies, it is OK to say that you’re a feminist, full stop. You don’t have to twirl your hair and stamp your toe delicately into the ground and sweet-talk that maybe you guess it’s OK that men and women be treated equally…

You can call yourself or not call yourself whatever you want, but consider this. Nobody enjoys it more when a woman says she’s not a feminist than a misogynist. Nobody gets more gloatingly self-congratulatory about it, or happier about what “real” women don’t need than someone who doesn’t like women very much…

A woman will usually strike me as rather petty if she trashes the entire feminist movement just for the sake of making sure no one thinks of her as unattractive or unlikable. And a man will usually strike me as rather creepy if he downplays the importance of women’s rights or refuses to see the ways in which feminism benefits men tremendously. Complacency is just as self-righteous as belligerence.

There are many people who opt out of activism for very good reasons. Some have had terrible experiences with prejudice and for them, avoiding political discussions means avoiding deep and harrowing pain. I myself have had days—sometimes years—when I just did not want to think about my dwarfism in any political way. Constantly reminding yourself of all the narrow-mindedness out there is not a lot of fun. To those on the receiving end of bigotry, it’s perfectly fair to want a break from the tough stuff.

It’s also fair to take a more nuanced approach to politics, to believe in an idea but not the execution, or to question the usefulness of labels like “feminist” or “environmentalist.” But we would look cock-eyed at anyone who said, “I’m not into human rights, but—” And so I react with the same “WTF?” to anyone who goes out of their way to disassociate themselves with feminism, or any other social justice movement. In the words of my husband, “Why would anyone explicitly say they don’t like feminism? That’s like saying you don’t like democracy.”

And to those who still think feminism is inherently humorless and activism is overly serious, I direct them to a story featured in The New York Times in 1990, wherein feminist activists broke into toy stores and switched the computer chips of Talking Barbie and Talking G.I. Joe, which left the blonde roaring, “Vengeance is mine!” and the soldier musing, “Will we ever have enough clothes?”

(And for those of you who like your jokes a little bluer, there’s this and this.)

I very much want to reach those participants in the study, that majority of North Americans who associate activists with repugnant rage. This issue is of particular concern to me because, among my closest friends and family, no one has ever called me soft-spoken.

Toward the end of my senior year in high school, I got wind of a rumor that I was going to be voted “Most Argumentative” in the yearbook. As soon as I heard about this, I campaigned for it. “You’re not voting for me? Why the hell don’t you think I’m the most argumentative?!” In jest, of course.

But not without truth. I had published my first angry letter to the editor at 14, followed by a couple more over the years. I spoke at school board meetings and political rallies. When I heard a speech I gave described by a family friend as overflowing with “righteous indignation,” I could not have been more pleased. It felt in part like a revolution against old-fashioned gender roles—because everyone knows a woman who talks too much is castrating, while a guy who can command the room is powerful—but mostly it just felt like me. When I like something, I love it to pieces, and when I don’t, everyone braces themselves for a rant. Assertiveness over insecurity. Honesty over likability. I don’t care what you think, anyway. I am woman. Rar.

Years later, as I began writing for wider audiences, I began wondering if my Medea-like rage had ever changed a single mind. Righteous indignation sounds passionate to those who already agree with you, but what if my I-HAVE-NO-TOLERANCE-FOR-INTOLERANCE approach had actually scared off someone who may have been willing to hear my argument in lowercase letters? I refuse to back down, but I don’t want to threaten anyone, either.

Make no mistake, I still love to argue with righteous indignation at all hours of the day with anyone willing to engage me. (As I explained to my sleepy-eyed partner in the middle of a rant about cultural appropriation one morning before work, “Sorry, honey, but you married a walking manifesto.”) But whenever it comes to public debate, I try to remember to put on the brakes and ask myself, Do I want to silence my opponents or convince them?

And if the answer is the latter, then Desmond Tutu certainly said it best: “Don’t raise your voice—improve your argument.”