(Image by Ellen Forsyth used under CC 2.0 via)

(Image by Ellen Forsyth used under CC 2.0 via)

Perhaps you are looking for gifts for little ones this holiday season. Or perhaps, like me, you simply know a staggering number of kids who will all have birthdays in the coming year. For either scenario, here is a sample of excellent—i.e., not boring or ugly—picture books that help raise diversity awareness through reading. All of these books have been featured in my workshops for pre-school teachers about helping minority children feel represented and teaching all students to see minority kids as their equals. They are divided into five categories based on objective.

***

Books That Know Not Every Family Is Upper/Middle Class with a White, Straight, Biological, Married Mom and Dad… The most delightful thing about pre-schoolers is that they have almost no idea what “normal” means. Of course they are surprised by the extraordinary, but they don’t place value judgments on it until someone older teaches it to them. Critically analyzing the media images and stories kids consume is crucial because the media not only educates them about the world beyond their doorstep, but it instills them with subconscious ideas about what kinds of people society believes deserve to appear in books, film, and television. Kids are of course individuals and some may be temperamentally predisposed toward narrow-mindedness, but a preemptive strike against prejudice never hurt anyone.

Tell Me Again About the Night I Was Born by Jamie Lee Curtis (available in German & Spanish) – A story of adoption as told from the point of view of the child. “Tell me again how the phone rang in the middle of the night and they told you I was born. Tell me again how you screamed. Tell me again how you called Grandma and Grandpa, but they didn’t hear the phone ’cause they sleep like logs…”

A Chair For My Mother by Vera B. Williams – A story that portrays poverty without uttering the word. The daughter of a single working mom tells of the day they lost everything they owned in a house fire. They’ve been saving up every spare cent they have to buy a big comfy armchair for their new home ever since. In the end, Mom finally has a place to lie back and rest her sore feet when she comes home from work at the diner, and her daughter can curl up to sleep in her lap.

Two Homes by Claire Masurel (available in French & German) – A boy proudly shows off his two homes. “I have two favorite chairs. A rocking chair at Daddy’s. A soft chair at Mommy’s.” The parents are portrayed as having nothing to do with each other, while always beaming at their son. “We love you wherever we are, and we love you wherever you are.”

The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats (available in Spanish) – Ezra Jack Keats was one of the first American illustrators to feature everyday black children in his stories. All of his books portray kids growing up in inner city neighborhoods. This is a brilliantly illustrated, very simple story about a boy enjoying freshly fallen snow in every way possible.

Susan Laughs by Jeanne Willis – Written in verse, Susan swings, makes faces, sings songs, plays tricks, splashes in the water, rides on her dad’s shoulders, races in the back of a go-cart. Susan also happens to use a wheelchair.

What Makes A Baby by Cory Silverberg (available in German & Spanish) – A book about reproduction (sperm, egg, uterus) that leaves out gender (mom, dad, man, woman). No matter how many people want to ignore it, plenty of kids have been born via IVF, surrogacy, and to LGBTQ and intersex parents. This book allows those kids to have a conversation about where they came from, while emphasizing that your family is the people who were waiting for you to come into the world.

***

Books For Extraordinary Situations That Have To Be Explained… These stories get into the specifics of certain disabilities, conditions and diverse backgrounds, but there is no reason they should not be read to every child.

Thinking Big by Susan Kuklin – This book is out of print, but well worth the search, portraying a day in the life of an 8-year-old girl with achondroplastic dwarfism. She is great at painting, but needs stools to reach things at home and school. She has friends who hold her hand so she won’t get left behind on hikes, but she talks openly about the kindergartners who call her “baby.” She loves going to Little People of America meetings, but she loves being at home with her mom, dad and younger brother best of all. This book accompanied me from pre-school to fifth grade, read aloud by my new teacher to the class at the beginning of the school year in order to explain why I looked different from the others and to encourage my classmates to be upfront with their questions.

I Have A Sister My Sister Is Deaf by Jeanne Whitehouse Peterson– A day in the life of a hearing girl and her deaf sister. They play, argue, and help each other out, while explaining deafness as a mere difference in terms young kids can understand. The story has a gentle, poetic rhythm. On a deer hunt, the narrator explains, “I am the one who listens for small sounds. She is the one who watches for quick movements in the grass.”

The Black Book of Colors by Rosana Faría (available in French, German & Spanish) – Like the illustrations, everything is black for Thomas, so when it comes to colors, he smells, hears, and feels them. “Red is as sweet as a strawberry, as juicy as a watermelon, and it hurts when it seeps out of a cut on his knee.” The images are embossed for the reader to touch. The Braille alphabet is provided at the back of the book.

People by Peter Spier (available in French & German) – A superbly illustrated celebration of human beings and cultures all around the world. We have different skin colors, noses, hair styles, holidays, favorite foods, alphabets, hobbies, and homes, but we’re all people. It should be noted that this might be a bit of an information overload for children under 4.

***

Books About Moments When Diversity Is Considered Disruptive… These books empower kids who have been teased or interrogated for standing out. They can also be used to teach a bully or a clique how to understand and accept harmless differences. Some teachers rightly express concern over introducing the problems of sexism or racism to a child who has never seen a boy in a dress or a black girl before. Doing so could foster the notion that we should always associate minorities with controversy. Save them for when conflict does arise, or when the child is old enough to start learning about history and intolerance.

Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman (available in Arabic, German, Panjabi, & Urdu) – Grace is a master at playing pretend. When her class decides to put on the play Peter Pan, she’s told by some know-it-all classmates that she can’t because she’s a girl and she’s black. She shows ’em all right.

And Tango Makes Three by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell (available in German) – Penguins Silo and Roy live in a New York zoo and are utterly inseparable. The zookeepers encourage them to take an interest in the lady penguins so that they can soon have baby penguins, but to no avail. Silo and Roy build a nest together and end up adopting an egg. When Baby Tango is born, the three of them couldn’t be happier.

You Be Me – I’ll Be You by Pili Mandelbaum (available in French) – A biracial girl tells her white dad she wishes she looked like he does. Dad explains that he is milk and Mom is coffee, and she is café au lait. He says she is beautiful and sometimes he wishes he looked like her. Soon they’re dressing up in each other’s clothes, she’s braiding his hair, and he’s powdering her face. She wants to go into town and show Mom. On the way, they pass by a beauty shop and Dad points out how many white women are curling their hair and tanning their skin, while so many black women strive for the opposite.

“Sick of Pink” by Nathalie Hense (currently available only in German, French, Japanese, Norwegian & Portuguese) – The proud musings of a girl who likes witches, cranes, tractors, bugs, and barrettes with rhinestones in them. She knows boys who sew pretty clothes for their action figures and who paint daisies on their race cars. When grown-ups shake their heads and tell them, “That’s for girls!” or “That’s for boys!” she asks them why. “That’s just the way things are,” they tell her. “That’s not a real answer,” she deadpans.

***

Fairy Tales Beyond White Knights and Helpless Princesses… Even the most iconoclastic of people have their fantasies of love and heroism shaped by folklore. Yet the idea of revising Western fairy tales to make them less stereotypical has been met with a strong backlash. Whether or not you think it’s appropriate for kids to read Sleeping Beauty, Little Black Sambo or The Five Chinese Brothers, there is no harm in providing them with additional legends about love, valor and wisdom to make our cultural heritage more inclusive.

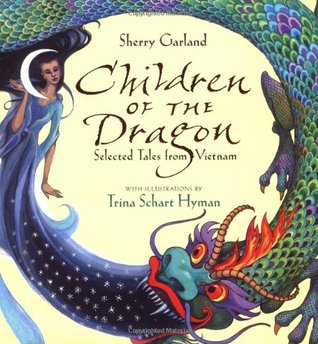

Children of the Dragon by Sherry Garland – Selected tales from Vietnam that rival any of the Grimm’s fairy tales in adventure, imagination and vibrancy. Many of the stories are supplemented by explanations of Vietnamese history that provide context.

Sense Pass King by Katrin Tchana – A girl in Cameroon outsmarts the king every time. Besides being one of the greatest illustrators of the 20th century, Trina Schart Hyman was a master of ethnic and socio-economic diversity in her many, many picture books.

Tam Lin by Jane Yolen – A Scottish ballad wherein a young maiden rescues her true love from the clutches of the evil faerie queen. In the end, she wins both his freedom and her clan’s great stone castle back. Not suitable for easily frightened children.

Liza Lou and the Yeller Belly Swamp by Mercer Mayer – A fearless girl triumphs over a ghost, a witch, a troll and a devil on her way to Grandma’s house in the bayous of Arkansas. Some of the best illustration there is. Think Little Red Riding Hood had she managed to outwit the wolf on her own.

The Talking Eggs by Robert D. San Souci – A Cinderella story of sorts set in the backwoods of the South. An elderly wise woman uses magic to help a kind, obedient girl escape her cruel mother and spoiled sister. In the end, she rides off to the big city in a carriage. (With no prince involved, this one passes the Bechdel test.)

King and King by Linda de Haan (available in Czech, Dutch & German) – It’s time for the prince to hurry up and get married before he has to rule the kingdom, but every princess who comes to call bores him to tears. The very last one, however, brings her utterly gorgeous brother, and the king and king live happily ever after.

The Paperbag Princess by Robert Munsch – After outwitting the dragon, Princess Elizabeth rescues the prince only to be told that her scorched hair and lousy clothes are a major turn-off. She tells him he is a bum. “They didn’t get married after all.” She runs off into the sunset as happy as can be. I have yet to meet a child who does not love the humor in this story.

***

The Best Book on Diversity To Date…

Horton Hatches The Egg by Dr. Seuss – A bird is sick of sitting around on her egg all day, so she asks Horton if he would mind stepping in for just a minute. He is happy to help, but the bird jets off to Palm Beach the minute she is free. Horton continues to sit on the egg while awaiting her return. He withstands the wind, the rain, a terrible cold, and three hunters who insist on selling him and the egg off to the circus as a freak show. Throughout it all he reminds himself, “I meant what I said and I said what I meant. An elephant’s faithful, one hundred percent.” After he becomes a media sensation, the bird comes back to claim her prize.

Whenever I used this one in the classroom, I would ask the kids whom the egg belongs to. The 3-year-olds, with their preliminary grasp on logic, would always give the black-and-white answer: “The egg belongs to the bird because eggs go with birds.” The 4- to 5-year-olds would invariably go the other way, plunging into righteous indignation over the injustice of the bird’s demands: “The elephant! The egg belongs to the elephant because he worked so hard and he loved it so much and she just can’t come back and take it!” In the end, the egg cracks open and out flies a baby elephant bird, who wraps his wings around Horton. This is Seuss at his best, showing that loyalty makes a family.

Tags: Art, Diversity Awareness, Education, Equality, Fairy Tales, Gift Ideas, Teaching

(Image ©Ines Barwig)

(Image ©Ines Barwig)

(

(