(Via)

(Via)

“Pregnant mothers should avoid thinking of ugly people, or those marked by any deformity or disease; avoid injury, fright and disease of any kind.” So advised doctors in the 1920 parenting manual Searchlights on Health. Eugenics was all the rage back then, but it had hardly come out of nowhere. The ugly laws of the 19th and early 20th centuries prohibited, for example in Chicago, “Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares, or public places.”

Under these laws, poor and homeless people with disabilities suffered the most. The class system gave those from affluent families, like Helen Keller, a better shot at being exempted. But before the disability rights movements of the 1970s, countless disabled children were abandoned by their families in orphanages and asylums, and were thus condemned to grow up to either join the circus or become the vagrants these laws targeted. Abandonment, rejection and the resulting invisibility in society is an ableist tradition of astounding resilience. Because just how far have we come in the past hundred years since doctors and municipalities advised not talking about or looking at disabled people?

This week Slate magazine features two articles by Barry Friedman and Dahlia Lithwick, asking readers to consider “what is left for the progressive movement after the gay rights victory at the Supreme Court.” Arguing that liberal activists have developed tunnel vision, focusing almost exclusively on gay marriage and nothing else, they trumpet issues that deserve attention along with marriage equality. Their list spans two articles, covering all sorts of social causes, from ending the death penalty to protecting the environment to improving child-care funding and education to marijuana legalization. Nowhere in either article do they mention disability rights.

This very same week Slate also kicked off a blog about Florida by Craig Pittman with an opening article called, “True Facts About the Weirdest, Wildest, Most Fascinating State.” Among the facts that apparently render the Sunshine State weird are the python-fighting alligators and “a town founded by a troupe of Russian circus midgets whose bus broke down.” On the day of its release, Slate ran the article as its headline and emblazoned “A Town Founded By Russian Circus Midgets” across its front page as a teaser.

Face-palm.

Friedman and Lithwick have nothing in common with Pittman except that they also write for Slate, a news site written by and for young liberals. And that their articles remind me of what I’ve come to know and call Young Liberal Ableism.

That is, there are two ableist mentalities not uncommon among young liberals:

1) Uncomfortable Silence: the tendency to skirt issues of disability, especially compared to other social issues, because disability threatens two things young liberals unabashedly embrace – being independent and attractive. (“Independent” and “attractive” rigidly defined, of course.)

2) Sex with Circus Midgets: the sick fascination with physical oddities that objectifies and/or fetishizes people with atypical bodies or conditions. (I’ve discussed this in detail here.)

Both mentalities see any disabled people they hurt as acceptable collateral damage.

Here’s the thing about dealing with all this. You get used to it, but not forever and always. Sometimes it rolls off your back, sometimes it hits a nerve. This time, seeing a magazine as progressive as Slate brandish RUSSIAN CIRCUS MIDGETS on its front page while leaving disability rights out of its social justice discussion brought me right back to college, where friends of friends called me “Dwarf Emily” behind my back and someone else defended them to my face. Where classmates cackled about the film Even Dwarfs Started Off Small—“because it’s just so awesome to see the midgets going all ape-shit!”—but declined my offer to screen the documentary Dwarfs: Not A Fairy Tale. Where a gay professor was utterly outraged that her students didn’t seem to care about immigration rights or trans rights, but she never once mentioned disability rights. Where an acquaintance asked to borrow my copy of The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers, but awkwardly turned down my offer to lend her Surgically Shaping Children. Where roommates argued vociferously that they would rather be euthanized than lose the ability to walk. Where jokes about dwarf-tossing were printed in the student paper.

I won’t go into certain crude comments that involved me personally, but I will say that when a friend recently, carefully tried to tell me about how shocked he was to find a certain video of dwarfs in a grocery store, I cut him off and said, “Lemme guess, it was a dwarf woman porn video? That’s one of the top search terms that bring people to my blog.”

For a little more than a decade, I’ve lived on one of America’s most liberal college campuses and then in one of the world’s most progressive cities. I have never met so many liberal people at any other time in my life and I have never met so many ableist people at any other time in my life.

This is not to ignore all those I’ve met who, despite their lack of experience with disability, ask carefully constructed questions and consistently make me feel not like a curious object but like a friend who is free to speak her mind about any part of her life experience. And some young liberals are doing awesome work for disability rights and awareness. But when a journalist and mother of a disabled twentysomething recently said, “No one wants to talk about disability rights – it’s not seen as sexy enough,” I knew exactly what she was talking about.

In 2009, when the pretty darn liberal Huffington Post reported on Little People of America’s call on the FCC to ban the word “midget,” the majority of commenters snidely remarked, “At least they can get married.” There was truth to this, but I found it telling that not a single commenter on the left-wing blog considered that the word “midget” could be hurtful. Everyone instead decided to play Oppression Olympics.

Understand that I will never say that among liberals disabled people are worse off than other minorities or that ableism is the “last frontier” in human rights. It’s not. Even if I believed it to be true, it would be impossible to prove and fighting for the crown of Superlative Suffering doesn’t do anything but imply that there are those against whom you wish to compete. I don’t want to compete with anyone.

Nor do I assume that anyone who uses the word “midget” is bigoted. Many who use antiquated terms are honestly unaware of their potential to hurt. (It wasn’t until two years ago that I learned that referring to the Sami-speaking regions as “Lapland” can be very offensive to those who live there.) And there is no minority on earth whose members agree unanimously on a name. “Little people” makes me cringe almost as much as “midgets,” while my husband winces whenever I use the German word for “dwarf.” Labels are only half as important as the intentions behind them.

But when young liberals insist that no one can be expected to know that “midget” is hurtful, there is something particularly perverse about hearing dehumanizing beliefs and ideas come from the mouths of those who pride themselves on their open-mindedness and diversity awareness. Or whose own experience of marginalization would logically render them a better candidate for empathy. In the words of Charles Negy, bigotry is an unwillingness to question our prejudices.

Why do I call it Young Liberal Ableism and not just Young Ableism? Because certain liberals could learn a thing or two from certain conservatives about facing disability and illness. Consider the stereotype of the small-town conservative who proselytizes about etiquette and tradition, and goes into a tizzy over the idea of two men kissing or a woman not taking her husband’s name or her neighbors speaking another language or a singer using swear words. But for all the types of people she does not want to accept in her community, she is fiercely dedicated to her community. She spends a good deal of her time going to church and checking in on her neighbors, and stays in contact with those who are physically dependent, sick or disabled. As patronizing as charity can be, many young conservatives have been raised to send get-well cards, bake pies, and call on neighbors and relatives who are stuck at home or in the hospital. They’ve been raised to believe that it’s the right thing to do.

Many young liberals, meanwhile, have been raised to analyze their problems and personalities to the point of vanity, question moral traditions to the point of moral relativism, and feel free to do what they want to the point of only doing what they want. They believe that anyone is welcome to live in their town, but they’ll only socialize with those they deem interesting.

I’m stereotyping of course. But it’s a fact, not a stereotype, that in the U.S. liberals are less likely to donate to charity, less likely to do volunteer work, and less likely to donate blood than conservatives.

Ultimately, it does not matter whether you call yourself “liberal” or “conservative,” left-wing or right-wing. There are Ayn Rand conservatives who insist that compassion is “evil,” and there are liberals who work tirelessly in low-paying jobs at non-profits and social agencies that do as much good as any charity. There are those of all political stripes who make large charitable donations but also want everyone to know about it, and there are those who don’t know the first thing about politics but know everything about empathy. We are far more complex than our politics give us credit for.

The goal should be to never become too self-congratulatory about our politics or morals, as Friedman and Lithwick warn. But in response to their call for issues progressives specifically need to pay to attention to, I do have a wish list going:

How about young liberals fighting to make sure dwarf-tossing is banned around the world?

How about facts instead of factoids when it comes to communities founded by dwarf entertainers who have been socially isolated by ableism and fear life-long unemployment?

How about young liberals continuing to fight for the U.S. to ratify the U.N. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities?

How about young liberals debating the Supreme Court’s 9-0 ruling last year that religious organizations are exempt from the Americans with Disabilities Act?

How about young liberals talking more about the astronomical rates of violence against intellectually disabled people, rather than just sneering at Sarah Palin’s complaints about the word “retard”?

How about young liberal bloggers trying to understand physical disability and illness as often as they try to understand depression and social anxiety?

How about our seeing a lot more women with dwarfism starring in romantic comedies than in porn movies?

How about more young liberal discussions about real dwarfs than Tolkien Dwarves?

In issuing these demands, I’m of course terrified of appearing too self-interested. Politics is all about trying to square the selfishness of What about ME?! with the fairness of Everybody matters. Sometimes sticking up for your own rights is easier than sticking up for someone else’s. Sometimes it’s the other way around. All of us, liberals and conservatives, should value trying to do what is right rather than what is easy.

Tags: Ableism, circus freak, Conservative, Disability, Dwarfism, Dwarfs, Intersectionality, Liberal, Midget, Minority Rights, Sick Fascination, Slate, Ugly Laws

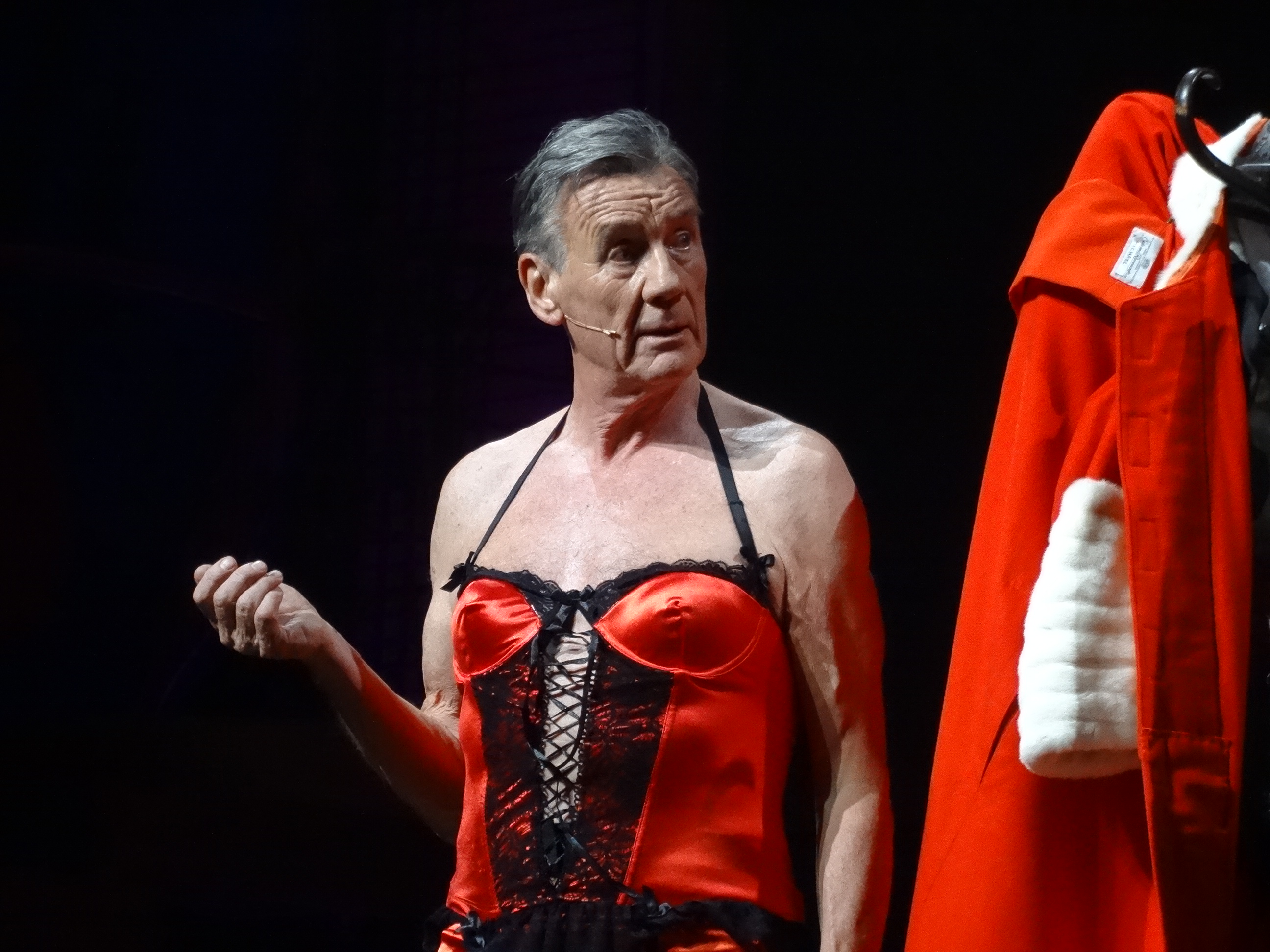

(Image ©Laura Swanson, used with permission)

(Image ©Laura Swanson, used with permission)